Ruston Kelly shares his story at Workplay on Saturday

Ruston Kelly’s career began with a BMG publishing deal in 2013. He had cuts on records by Tim McGraw, Josh Abbott Band and Hayes Carll before releasing his first EP of his own, Halloween, in 2017.

Dying Star was one of 2018’s brightest moments in Americana. Kelly calls the debut EP the prologue to his story, while the first full-length serves as chapter one. As the audience jumps into chapter one, it finds Kelly recovering from drug addiction by withholding none of the failures that came with it; “Blackout” and “Faceplant” are songs about just that.

In the music video for “Son of a Highway Daughter,” Kelly earnestly figure skates; a skill that he perfected through six years of intense training. He once fancied himself an Olympian before discovering his penchant for songwriting. Ahead of his first headlining show in Birmingham, he talked about that background and how it led him to the guitar. He talked about what role music plays in his path to recovery, and he revealed that his favorite team is a familiar one to many of the people that will be in the audience on Saturday.

How did you transition your career from publishing into writing for yourself and doing your own thing?

I was somewhat strategic about it. Performing songs for people and making records…I knew that I was going to do that since I was a kid. I was also broke and needed some money. [laughs] That was step one. I felt like if I could get my foot in the door with someone like BMG, which, at the time was John Allen – he was the guy that signed me there – he was also responsible for discovering Ryan Adams. He knew what moves we were going to make. I had a few people act as quasi-managers for a while to help me figure some [expletive] out, send me to rehab and really take care of me and my career; help me to see what it is that I really wanted to do.

Lucie Silvas cut a version of a song that you recorded on Dying Star [“Just for the Record”]. How do you feel those versions compare and complement one another?

I think a good song is a good song no matter how you do it. And I think she does a great job at it. The melody and some of the initial words kind of came out of my mouth first, so to me, it’s a male song. So her version is cool to hear because it seems to be an alternate opinion or an alternate sentiment from a woman’s perspective. I think that’s pretty cool. I really like her version.

Kenny Chesney nearly cut another track on this record – “Trying to Let Her.” As you forge your own path, do you think that other people recording songs that you’ve written is also a path or is it now more about you doing your own thing?

If someone wants to record my song, they can go ahead and do it. I’ll always have my version of it and they can’t take that away from me. All that it’s really going to do, if it’s successful, is make me some money, and I’m not opposed to that [laughs]. That’s what we call “mailbox money.” I may not be in the business of writing songs for other people, but if I write a song and someone else wants to record it while I’m on tour, that’s great. When I come back home, there’s a check in the mail. I’m fine with that.

Kind of like that Spotify check?

Exactly.

Does writing and recording about your path to recovery make it easier to maintain or does it feel more like an obligation to help your audience find their own path?

That’s a good question. It’s the former, definitely. It took me a long time to figure out what it was that I wanted to do; more so, not “what,” but “how.” And I think substance abuse, for whatever reason, whether that was a mental imbalance or fear of this or fear of that – who knows what’s laying deep in the psyche that would make someone want to continually abuse themselves. It took me a little while to get my personal rhythm and balance right. What’s interesting is that art and creating art was always a way for me to understand myself and feel, I guess, safe in a lot of ways – to create to relieve. I wouldn’t say that it’s ironic, I would just say that it’s special that my first thing that I was saying to the world is that, and that my first fans are people that I’m assuming are getting the same relief from listening to it that I did from writing it. I think that’s a really special thing.

Who had the idea for the “Son of a Highway Daughter” video and were there ever reservations about how an earnest video like that would be received in Nashville?

[laughs] As far as how it was going to be received in Nashville, I could give two [expletive]. But when it comes to actually executing the video, it was actually Stephen Kinigopolous and Alexa King – the brother and sister team that have done all of my videos – it was their idea. I had brought up the fact that I really wanted to ice skate in a video. I’d always wanted to do that. But I wasn’t sure how to pull it off – it was like, should it be a joke? Should it be Will Ferrell a la Blades of Glory? That’s what it was going to be up until the day of the shoot. And then something was like, “I feel like if we’re going to do this, let’s do it like no one else has done this before. Let’s be really serious about it and give my best artistic, physical performance of this song.” And it was really challenging. I also quit smoking to do it because there’s no way I could do it while I was smoking.

Have you maintained that? Are you still off the cigarettes?

I still am off the cigs. I love cigarettes; I always will.

They’re amazing, right?

They are! I love ’em. I would try to quit before, and I’d say [expletive] like, “I don’t like cigarettes anymore.” Or, “They smell.” But really I do like cigarettes, and I do like the way they smell, I just can’t smoke ’em anymore.

I love the way someone smells when they’ve been smoking and it’s cold outside and it lingers…

Dude. Same. But I think we’re in the minority because I think most people think that smells like straight garbage.

Do you think Dierks Bentley ripped off the skating video for his tour promo?

[laughs] I don’t think he ripped it off. I’m not sure he’s aware enough of me, but I do know a lot of people commented on it. “You ripped Ruston off.” I’ve run into him a couple of times; but I wouldn’t even consider us colleagues. We’re in two different styles of music. I think he’s a genuine guy; I don’t think he’d purposely rip off anything. It’s probably an accident. Also, it’s kind of a funny thing to joke about – the play on masculinity and femininity when a guy ice skates – because it’s one of the most challenging sports in the world.

How long did you train as a figure skater and how far did you take the sport competitively?

I trained for – from the time I was eight until I was 14. So six years. I won competitions and [expletive]; regionals and I went to nationals. I went to Junior Olympics. I had aspirations to really be an Olympian and that’s what I was training for. Part of what was so exciting about skating was being able to physically move to music that moves you. I moved away from home to do it, and I moved in with a husband and wife Olympic coaching team. The wife was having an affair with one of her students, and they decided to tell me that first. It was weird and awkward. If you think the music business is [expletive] up, the skating world is extra [expletive] up.

So I started playing guitar out there and learning how to play guitar as a way to distract myself from being away from my family and also dealing with stuff that felt way above my maturity level. It forced me to grow up a bit. But it also taught me how to feel safe in a chaotic environment, whether that was of my own making or peripheral.

Your dad has played with you a lot, and I guess he’s on the record, too. Is working with someone that close to you easy?

Yes and no. It’s also my dad. There’s a lot of dad element; father/son types of things that we have to navigate that aren’t normal to have out in a working environment, especially not in a creative working environment. But I would say that overall, it’s so worth it. My sister also comes out and she’ll sing with me from time to time. When I step back in the middle of a song in front of a bunch of people and I’m looking over and I see my dad and my sister next to me, that’s something I wouldn’t trade for the world. It’s a really special thing.

At some point, you actually lived briefly in Alabama. What part of the state were you in and for how long?

I lived in Alabama – in Mobile – when I was young. We probably lived there a few years. My dad is partly from Alabama. His family is from Jackson, Alabama. We actually lived in Fairhope for a few years. I went to Spanish Fort Elementary School. I don’t know if this is faux pas or not, but we’re a Roll Tide family.

Are you actively an Alabama fan or it just a causal thing?

Yes, actively. My dad and his dad used to watch Alabama football when Bear Bryant was coaching. That was a family thing. We’d go to a game once a year. My dad started watching with my older brother and they would go to games. Then I started watching with them. Unfortunately, with touring I haven’t been able to keep that tradition alive, but I still stay up with it.

Have you made it down in recent years for a game?

Ahh, man. The last game I was able to go to was probably four years ago when they played Mississippi State and completely demolished them. My brother and dad…they went to one this past season.

What are the three best metal records of all time?

Oh, that’s a good question. I would say Slayer’s Reign in Blood is one. I would say The Great Southern Trendkill by Pantera is one. And then for the third, I would say The Apostacy by Behemoth was pretty good.

But I mean, I guess I feel like it would feel obligatory for me to say that Venom’s Black Metal is one of the best metal records ever because it helped defined an important subgenre of metal.

Chris Carrabba [of Dashboard Confessional] joined you for the show at the Basement East in Nashville. How did you guys meet and how did that collaboration happen?

He did. We had a mutual friend, and I actually met him when he did two nights at the Basement East. This was like two years ago before I knew I could sell any tickets; before I made Dying Star. We had a mutual friend that used to tour with Chuck Ragan who was a mutual friend of his, and we were like, “Oh, we should all write sometime.” So we just exchanged info, and Dying Star came out and he texted me out of the blue – we hadn’t talked in probably a year or so – and he was like, “Holy [expletive]. This is one of my top five inspiring records of all time. I would love to sit down and write with you.”

So I was like, “Well, I’m playing the Basement East in a few months. Why don’t you come sing ‘Mercury’ with me?” And he was like, “Holy [expletive]. I would be honored.” And I’m freaking out because I grew up listening to Dashboard; I learned how to play guitar, learned how to songwrite by listening to all of his records. For us to exchange compliments on the meaning of each other’s work was surreal.

Halloween worked as one connected story all the way through. It seemed like a very deliberate record. Even the skits moved the story forward. Do you enjoy crafting a record that way or is it more practical to choose your best work and put it all together as a collection?

No, I think you nailed it. I’ll always make records that are a story. I think that each record is going to be reflective of a chapter in my life. I look at Halloween as the prologue; I look at Dying Star as chapter one. And this next record is going to be chapter two. Everything was truly deliberate. I took this little field microphone out to do all of the things that – I did all of those soundbites between the songs on Halloween myself. And if it didn’t read or listen as a story; if it didn’t offer a narrative of some sort, I wouldn’t feel like I accomplished what I wanted to do.

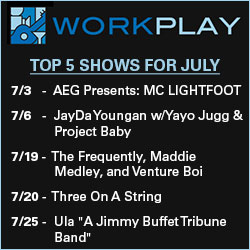

Ruston Kelly comes to the Workplay Theatre on Saturday, March 16. Doors open at 7 p.m. and the show begins at 8 p.m. Charli Adams opens. Tickets are $15.