Wye Oak find no easy answers on The Louder I Call, The Faster It Runs

Jenn Wasner talks the anxiety and self-actualization of the duo’s latest album.

To hear Wye Oak tell it, there are at least two ways to interpret the title of their latest studio album, The Louder I Call, The Faster It Runs. For Andy Stack, one half of the indie duo, it’s about chasing after something that only becomes more elusive the harder you try to catch it. For Jenn Wasner, Wye Oak’s other half, it’s about calling for help — but by calling out, you makes it easier for what you’re hiding from to find you.

Both interpretations are somewhat bleak and fatalistic, which at first seems to contrast the album’s shimmering, often gorgeous pop. But listen long enough and you’ll hear that undercurrent of anxiety — maybe in a particularly queasy synthesizer line, maybe in Wasner’s soul-searching lyrics — that centers on the difficulty of separating your self-image from how other people view you.

“You could even say that the record itself is a metaphor for that,” Wasner says. “I put this thing out into the world, but it brings this attention with it when I release it that is a cause of a lot of this anxiety.”

Most of that attention, at least, has been positive. The Louder I Call, The Faster It Runs has been heralded as Wye Oak’s most realized album to date, following the guitar-free experimentation of their 2014 album Shriek and the collaged-together songwriting of 2016’s mini-album Tween. It’s a high water mark for the duo — ”the record we’ve wanted to make for our entire career,” Wasner says.

Wye Oak will perform at Saturn Birmingham this Friday, July 27, their first time in Birmingham since a 2015 collaboration with the Alabama Symphony Orchestra. Recently, Wasner spoke with Jefferson County Journal about her “visual” writing process, Wye Oak’s fragmented method of collaboration, and the “unsolvable question” at the center of the new album.

Jefferson County Journal: You approached many of your recent albums with self-imposed limitations. Shriek, for instance, was a record on which you abandoned guitars entirely, while Tween was built largely from old scraps of recorded material. With The Louder I Call, The Faster It Runs, it doesn’t seem like you started with any of those limitations. Was that the case?

Jenn Wasner: Yeah, that’s absolutely the case. Honestly, for the first time, that was the mission statement. We’ve been making records for over 10 years, and every record has been something of a learning experience for us, which I think is common for a lot of people who make records. But we both realized at this point in our career, we really felt like we’d gotten to the point creatively where we were able to make a record like this.

This time, we both just felt like we were at this point where we’re the best we’ve ever been in everything we do, and we didn’t feel like we needed to have any of those restrictions or limitations, which often are put in place to sort of spark a creative thread that we can follow. I think it’s the record we’ve wanted to make for our entire career, in some ways.

Jefferson County Journal: While recording this album, you moved back and forth between Marfa, Texas, and Durham, North Carolina. Did that have an impact on the way you and Andy collaborate?

Wasner: The way that we work, and the way that we’ve worked for a long time now, is that we have a lot of time and space independently of one another, where we’re working in our own separate studio environments. Then we supplement that with an incredibly concentrated amount of time where we’re working together in the same space.

One of the times I went to Marfa, and one of the times Andy came to North Carolina, and those were really short, condensed, one-week or two-week time periods. At that point, we’d had all the time for that on our own to figure out exactly where we were going and what needed to be done. In that way, we were able to figure out a lot of the creative threads that were a little bit more ambiguous while we were separate.

We’ve found that this process has worked really well for us, because both of those phases are a really important part of how we make our records sound the way that they do. We needed all that time independent of one another to experiment in our own zones without the other person’s critical ear. It’s something that we feel like definitely come to affect the way our records sound. I think at this point regardless of whether we live in the same place or not, it’s something we’re probably going to end up duplicating in the process.

Jefferson County Journal: The last time Wye Oak came to Birmingham, it was for a collaboration with the Alabama Symphony Orchestra and composer William Brittelle, reimagining songs from Shriek. That project took a very deconstructionist approach to your songs. Did approaching them that way help shape the way you write?

Wasner: That project is actually still ongoing! That was the first show of what became many shows. We ended up working with Bill [Brittelle] and a bunch of other ensembles around the country. We took it to Baltimore, to St. Paul’s Chamber Orchestra. We’re about to do something with the Metropolis Ensemble at the Hollywood Bowl in August. So that was actually the beginning of what turned out to be an extended collaboration with Bill. We’re making a record together of music that we wrote featuring us, that we also performed there.

It was a really wild experience. I wouldn’t trade it for anything, but it’s challenging every time and we’ve done it a bunch of times. Every time we do it, five minutes before the show, we’d be like, “Is this going to happen?” By some miracle, it always ends up working out, but it’s a tightrope walk for sure.

I would say that experience has shaped both of us. Just for example, on The Louder I Call, the song “My Signal” was my first stab at string arrangement, which I only undertook because we’d met a few world-class string players in our collaborations with those ensembles. … A song like that would never exist if I had not had the experiences playing with these different musicians from different backgrounds. That’s something that Andy and I want to incorporate into our music more and more.

Jefferson County Journal: Lyrically, The Louder I Call is pretty far-reaching, talking about the ways in which humans interact with each other and the difficulty we have in finding common perceptions of the world. But the songs also approach those big questions on a very personal level. When you’re writing about such massive themes, do you start on a macro level and then personalize it, or do you start with the personal side of the lyrics and then apply them to a grander scale?

Wasner: I feel like it’s a big more of an intuitive process than it is a conscious one. I would say that everything that I’m inspired to write down is something that comes initially from my own experience. But as a reflective person — and so much of songwriting is just observing and reflecting — I’m constantly collecting those kinds of ideas. After a while, enough ideas have sort of accumulated and seem to fit under a certain theme or umbrella that I get a sense of what should be grouped together.

I keep these really detailed notes on my computer. It’s kind of hard without showing it visually, but I group them together under these different, bolded headlines, and eventually, after I collect enough of them, it becomes clear that it’s going to turn into a song. I can copy and paste things around; it’s a very visual process. The specific, personal stuff comes first, but what I’m searching for while making it into a song is sort of a universal umbrella that it fits under, which points toward a broader idea or concept. It’s almost like putting together a puzzle or something.

Jefferson County Journal: This album is bookended by two tracks, “The Instrument” and “I Know It’s Real,” both of which focus on finding a sense of self-worth that isn’t tied to other people. What drew you to that idea as the thematic through-line for the record?

Wasner: Thematically, that’s huge — that’s like, the crux of the record. “The Instrument” is an introduction to that concept, where it addresses that we’re dealing with the idea of being seen as something [as opposed to] actually being that thing. People present themselves in a certain way, which does not necessarily mean that the substance [of how they present themselves] is going to be present. I also turn it back around on myself and ask myself the same questions, about how I think of myself as being a selfless person, or trying to be, but how much of what I do is really driven by fear and a sense of ego.

And then at the end of the record, after sort of exploring those concepts throughout the record, that song is a conclusion to the process of trying to figure out that completely unsolvable problem. The solution, or at least the temporary solution I finally settle on, is “going small,” finding a part of yourself that feels fixed — that feels stable enough that you can really hold onto it regardless of what’s going around you, that really feels anchored. For me, that is something that’s very personal, and that I feel is something that I need to hold onto as best I can to navigate the chaos of the world around me.

So putting those on the front and back of the record is very intentional. “The Instrument” is the beginning of that journey, and “I Know It’s Real” is the end of that journey. However, it’s not really a complete journey, because there’s no real, easy answer to any of these questions.

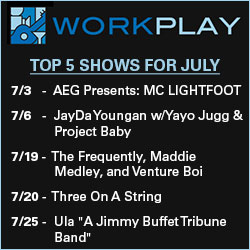

Wye Oak will perform at Saturn Birmingham on Friday, July 27. Madeline Kenney will open. Doors open at 8 p.m.; the show begins at 9 p.m. Tickets are $16 in advance and $18 the day of the show. For more information, visit saturnbirmingham.com.